A Standing Order of Pertussis Vaccine in Hospitals Boosts Protection

Mar 06, 2014

Gabrielle “Brie” Romaguera was born January 13, 2003 and passed away on March 6, 2003 at 52 days old as a result of a pertussis infection.

There is at least one family who is mourning today. Eleven years ago they lost their daughter Brie She was just 52 days old. Sadly she succumbed to a disease called pertussis, also known as whooping cough, which they knew little about at the time.

Since Brie’s death we’ve learned that changes made to improve the safety of the pertussis vaccine may have resulted in a vaccine that is not as effective. In the 1990’s the U.S.switched from whole-cell pertussis vaccine (DTP) to combined acelluar pertussis (DTaP) vaccine. A study in the June 2013 issue of Pediatrics looked at individuals born between 1994 and 1999 who received four pertussis-containing vaccines. The authors compared two groups during a 2009 and 2010 pertussis outbreak, some who received the older vaccine and some who received the newer DTaP. They discovered that those who received the newer vaccine had a six times higher risk of contracting pertussis due to waning immunity compared to those who received the older vaccine.

While vaccines are a very effective way at preventing disease, they’re not perfect. Pertussis vaccines typically offer high levels of protection within the first 2 years of getting vaccinated, but then protection decreases over time. In the case of pertussis, this also occurs with natural infection, meaning that even if you contract pertussis you do not retain any lifelong immunity and it’s possible to be infected again.

In general, DTaP vaccines are 80-90% effective in children with the highest protection following the fifth dose when 9 out of 10 kids are still fully protected. In each year following the last dose there appears to be a modest decrease in effectiveness. Still, five years after the last dose 7 out of 10 kids are still fully protected and the other 3 are partially protected. So how long has it been since some adults have been vaccinated? How much immunity do you suppose they have?

Since Tdap vaccines have only been licensed since 2005, we’re still investigating how protection may decline over time or might differ based on which vaccine was received during early childhood (i.e., DTaP or DTP). While it’s difficult to say how much immunity an adult may have if they have never received an adult Tdap booster, it’s suggested that those who receive the recommended adult Tdap booster are better protected.

As public health experts witness an upward trend of pertussis cases nationwide, we’re beginning to understand how low vaccination coverage among adults and adolescents, in combination with waning immunity from the newer vaccine, may be creating a health risk to the youngest members of our society. While pertussis is highly contagious and can be a dangerous illness for adults, it presents an even greater risk of hospitalization and death among infected infants like Brie. There are dozens of personal stories on the Shot By Shot website that detail the extreme suffering among adults, teens and infants. But what we know from the data is that pertussis is most severe for babies. The majority of pertussis deaths occur among infants younger than 3 months of age and about half of infants younger than 1 year of age who get the disease need treatment in the hospital.

As rates of pertussis infection have escalated, so has the public health effort aimed at combatting it. Since babies don’t complete the five shot DTaP vaccine series until they are toddlers, they remain at highest risk of complications. That’s why there’s an effort to increase pertussis vaccine rates in adults and adolescents, through timely Tdap boosters. The idea is to reduce the prevalence of disease in the community which may then decrease the number of infants who are exposed before they are adequately protected from the vaccine.

As rates of pertussis infection have escalated, so has the public health effort aimed at combatting it. Since babies don’t complete the five shot DTaP vaccine series until they are toddlers, they remain at highest risk of complications. That’s why there’s an effort to increase pertussis vaccine rates in adults and adolescents, through timely Tdap boosters. The idea is to reduce the prevalence of disease in the community which may then decrease the number of infants who are exposed before they are adequately protected from the vaccine.

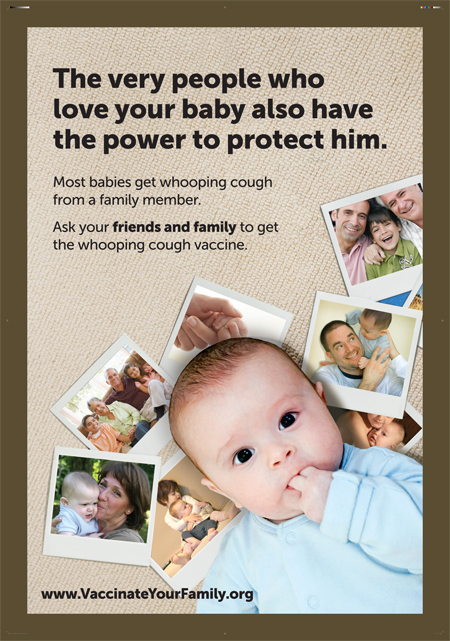

One thing that research has shown us is that babies who catch pertussis are often infected by a close family member. In fact, one study reveals that household members were responsible for 76-83% of transmission and mothers were specifically responsible for about 30-40% of cases. This is why there’s an effort to ensure that every newborn’s parents, grandparents, siblings and care-givers are up-to-date with their Tdap booster. The ACIP has even recommended that women get an adult Tdap booster vaccine while pregnant, and with each subsequent pregnancy, regardless of when their last Tdap vaccine was administered. It’s even advised that women consider getting vaccinated in their third trimester, when maternal antibodies can help provide their newborn baby with interim protection before the baby receives their own whooping cough vaccine at 2 months old. These first few weeks of life are critical, as was seen in Brie’s case. A baby is at greatest risk for contracting whooping cough in the first few weeks of life, but they’re also at an increased risk of suffering severe, potentially life-threating complications.

Unfortunately, policy changes are slow to take hold and not all expectant mothers are getting vaccinated during pregnancy. But research published today in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (AJOG) illustrates how small and simple changes in hospital procedures can make a big impact in ensuring that the mothers of newborn babies are adequately vaccinated. In a comparison of two private hospital facilities, this study determined that hospital implemented opt-in orders and standing orders for pertussis vaccination successfully boosted vaccine uptake among postpartum women. In the intervention hospital, the introduction of the opt-in order was followed by an 18% increase in postpartum vaccination. The follow-on introduction of a standing order for pertussis vaccination subsequently boosted vaccination rates to 69%.

Hopefully this research will encourage more hospitals to update their policies in order to emphasize the importance of adult Tdap boosters. Although it may take up to two weeks to build immunity as a result of the vaccine, and it’s still preferable for expectant moms to be vaccinated in their third trimester, offering parents the vaccine before they leave the hospital may help prevent another tragedy like Brie’s. This study simply reinforces the idea that if we continue to call for positive immunization policy changes that we can help to save lives.

Brie’s family knows there is nothing they can do to bring their precious baby back. But they have spent the past eleven years trying to share a life-saving message of immunization to others. This research supports the idea that if we give parents the opportunity to be vaccinated, either pre-delivery or postpartum, they will overwhelmingly decide that it is in the best interest of their child. And that choice may just save them their child’s life.

Related Posts

The Public Health Emergency (PHE) declaration is ending on May 11, but COVID remains a threat. The PHE was first declared in 2020 in response to the spread of COVID-19 to allow for special...

This post was originally published with MediaPlanet in the FutureOfPersonalHealth.com Winter Wellness Issue, and was written by Vaccinate Your Family. Are you more likely to get sick during the winter? Yep – more viruses...

Leave a Reply